By Michael J. Lewis | Dec. 7, 2019

As we now enter the 10th year of Instagram, the photo-sharing network, it is not too early to wonder about its effect on architecture. An architect friend recently showed a rendering of a hotel facade to her client who cried, “That’s my Instagram photo.” To dazzle on a five-inch screen, a building needs only graphic pizazz. But as this year’s notable buildings show, architecture involves a good deal more.

So much attention has been lavished on “Billionaires’ Row”—that clutch of residential towers now sprouting to the south of Central Park that includes a few 1,000-plus-foot prodigies—that a building as subtle as Robert A.M. Stern Architects’ 520 Park Avenue easily goes unnoticed. Unlike them, this 54-story apartment tower is an exceptionally well-mannered building that derives its forms from the gracious apartments of the prewar era, with their limestone cladding, bronze trim and vaulted lobbies. This is the New York vernacular, and for RAMSA it is not a straitjacket but a springboard.

Far more modest, but equally respectful to its urban context, is Saint Thomas/Ninth, a small but ingenious housing development in New Orleans. In a triumph of miniaturization, architects OJT shimmied 12 small houses onto a parcel zoned for three, thereby maintaining the city’s historic density while providing affordable housing (the entire project cost $2.5 million). The houses vary genially in form, but collectively they achieve the compact unity of a traditional neighborhood.

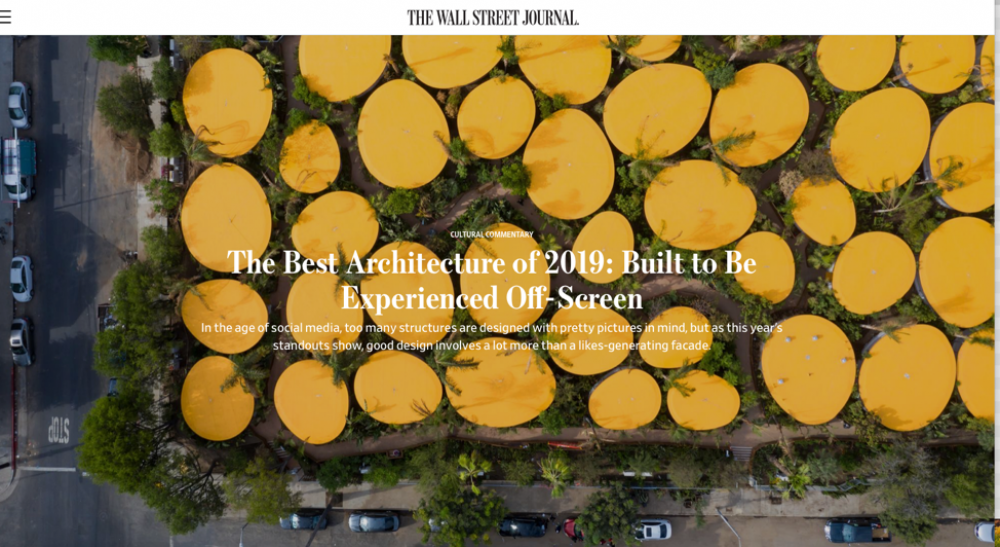

As the digital revolution transforms the workplace, the Madrid-based firm SelgasCano proposes a new kind of office building adapted to our new “nomadic workforce” of freelancers and flex-time workers. Their Second Home Hollywood in Los Angeles dispenses with traditional offices and cubicles to sprawl across a 90,000-square-foot campus of 60 one-story glass-walled pods, brimming with lush tropical plants. The result is neither office building nor botanical garden but an uncanny hybrid of both.

With the best Scandinavian design, arresting visual form is the result of the design process, not the beginning: Sensitive accommodation to human activity generates form. In the Heights Building, a public school in Arlington, Va., architects Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) pivoted five separate trays of space around a central spine, breaking up what would have been an overwhelming institutional block (180,000 square feet) into humanly scaled independent units.

Ada Louise Huxtable memorably dismissed Edward Durell Stone’s Kennedy Center in Washington as “a marble sarcophagus in which the art of architecture lies buried.” Steven Holl Architects has now enlarged that sarcophagus with The Reach, a trio of freestanding pavilions that do much to offset its aloof temple-like character. Seemingly set in a garden, the pavilions actually rest on a green roof, the largest in Washington, beneath which are 72,000 square feet of studio and performance space. The pavilions are of titanium-white concrete, an inspired updating of the traditional white marble of the neoclassical capital.

Unlike Holl’s free-form classicism, Christ Chapel at Hillsdale College, Michigan, gives us the real thing, classical architecture carried through with consistency and conviction. Duncan Stroik, who has already built half-a-dozen classical churches, draws freely here from Baroque, Palladian and Neoclassical forms to achieve spatial drama. The visitor approaches the twin-towered facade to enter through a domed porch, vaulted in brick, the first large brick vault built in this country in half a century. Three portals, inscribed Fides, Spes and Caritas (faith, hope and charity), lead to progressively grander spaces: first a small vestibule, then a generous narthex, and finally the soaring vessel of the nave, its coffered barrel-vault hoisted triumphantly on slender Doric columns.

It was a stroke of inspiration to render the interior white so as to make the gray columns stand out. This calls attention to their load-bearing role, reminding us that classical architecture is fundamentally the art of making construction beautiful, and that its fundamental expressive element is the column. At the same time this leads us to perceive the nave to be a longitudinal space when in fact it is nearly square, in effect an auditorium plan. In every respect—in construction, ornament and especially its siting—Christ Chapel sparkles, and shows that the rules of classical architecture are no more an impediment to imaginative design than the rules of grammar are to imaginative speech.

One cannot close the year without again saluting the TWA Hotel at New York’s JFK airport. Designed by Eero Saarinen and opened in 1962, it was America’s finest airline terminal. Now, as restored by Beyer Blinder Belle and added to by Lubrano Ciavarra Architects, it has been reborn as a hotel. One notices the clever touches, the rotary dial phone and vintage copy of Life magazine in every room, and might miss its greatest coup: the insulated glass that lets guests drift off to sleep in the middle of a busy airport—in absolute silence. Go and see it.

—Mr. Lewis teaches architectural history at Williams and reviews architecture for the Journal.